Accountancy Europe unites 1 million professional accountants that are qualified by, and registered, with our member bodies. They work as accountants, auditors and advisors: providing a wide range of services in diverse capacities and sectors. Read more here.

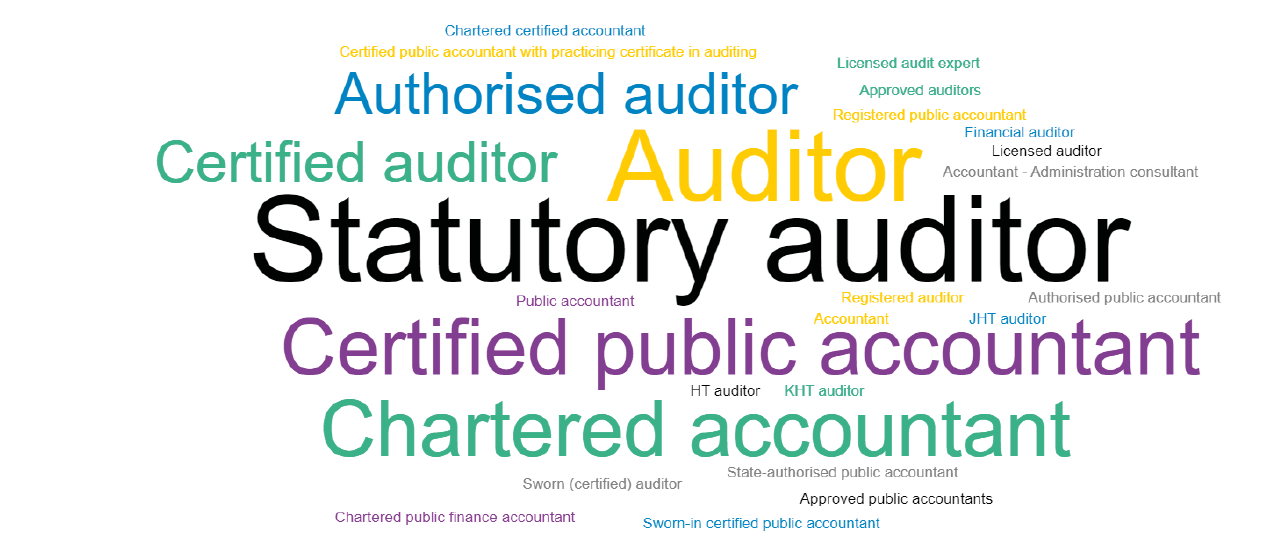

How the accountancy profession is organised varies across Europe. The main difference is between auditors who are regulated at EU level, and accountants and advisors, whom national governments decide on their regulation. This means that the EU protects the title ‘auditor’, defines how to qualify, and remain qualified and the reserved activities that only auditors can carry out. For accountants and advisors, there are vast differences within Europe on how matters are dealt with, for example protected titles, registration, professional bodies’ membership or public oversight.

Below we explain how access to the European accountancy profession is organised, particularly what it means to become an auditor. We have also gathered detailed information on how the profession is organised per country that you can check via our interactive map.

The audit profession is regulated. The EU Statutory Audit Directive 2006/43/EC (SAD) sets the minimum requirements that Member States must comply with. Because of this minimum harmonisation, they can have additional national requirements.

The audit profession is regulated. The EU Statutory Audit Directive 2006/43/EC (SAD) sets the minimum requirements that Member States must comply with. Because of this minimum harmonisation, they can have additional national requirements.

EU law protects the title ‘auditor’ so that it can only be used by people that fulfil all legal requirements to enter the profession. The EU also regulates which activities are reserved for qualified auditors, primarily signing off on the audit report. Due to the SAD’s minimum level of harmonisation, the reserved activities vary between Member States. Next to these reserved activities, it sets out included authorisations, where auditors are part of the limited number of professions that can perform these.

Qualifying as an auditor consists of 3 stages: 1) education, 2) experience and 3) examination. In addition to the below-mentioned steps, Member States may have additional requirements for qualification.

1. Education

A trainee must be of good repute and fulfill the initial education requirements. Namely, having attained a university entrance or equivalent level and complete a theoretical course. In some countries, such as the United Kingdom (UK), they can enter the profession directly after secondary level education and at the same time follow an educational programme.

2. Experience

The trainee must also complete a minimum of 3 years of practical training in auditing of annual financial statements, consolidated financial statements or similar financial statements. At least two thirds must be completed with a statutory auditor or an audit firm approved in any Member State.

3. Examination

Finally, the trainee must pass an examination of professional competence. The examination can be organised by for example a university, a professional body, or a public oversight authority. The examination must be recognised by the concerned Member State. In some countries, the trainee may also have to pass certain exams before entering the practical training, depending for example on educational background.

After obtaining the professional qualification, auditors 1) need to register publicly, 2) must participate in continued professional development 3) can or must join a professional body, 4) are subject to public oversight and 5) follow national requirements.

1. Must be entered in a public register.

The SAD lists the specific information which should be included in the register.

2. Participate in continued professional development (CPD)

To keep their qualification, auditors must participate in continued professional development, to maintain their theoretical knowledge. The SAD lists the minimum requirements including the main topics and sanctions when not complying. National requirements are often more stringent, requiring on average 40 CPD hours per year.

3. Become a member of a professional body (voluntary or mandatory)

Some national governments mandate new auditors to become a member of a professional body to be able to use the qualification and perform the reserved activities. In other countries this is voluntary. Professional bodies represent their members’ interests, but their national government or public oversight authority can also delegate responsibilities delegated to them.

4. Become subject to public oversight

Qualified auditors become subject to public oversight to ensure audit quality. The SAD assigns this to national audit oversight bodies, but Members States, or these national bodies can delegate certain tasks to professional bodies or other organisations. The national authorities cooperate at EU level in the Committee of European Auditing Oversight Bodies (CEAOB). Our survey Organisation of the public oversight of the audit profession in Europe offers a more detailed description of delegated activities per Member State.

The public oversight authorities are responsible for:

5. Abide by national requirements

Some countries also set extra requirements, for example obliging auditors to:

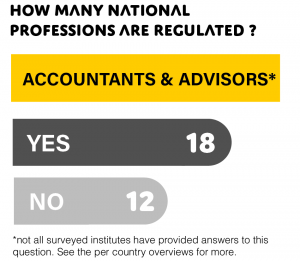

Member States can choose if, and how, they regulate professionals providing accountancy and advisory services. Belgium and France for example, regulate accountancy and tax services and protect the titles ‘accountant’ and ‘tax advisor’. In the UK neither are protected, so in principle everyone could call themselves ‘accountant’ and provide accountancy services.

Although providing accountancy services is not regulated on EU level, EU law contains some minimum requirements in the following directives:

Education of accountants and advisors is not harmonised in the EU. National regulators or professional institutes can, however, refer to the international education standards (IES)[1] if they choose to regulate the profession or are involved in providing education services. Like the requirements for obtaining the auditor qualification, the IES suggest requiring the candidates to complete initial professional education, assessment of professional competence, practical experience, and – after obtaining the professional qualification – continuing education.

According to our findings of how European countries deal with this, this is most commonly similar to auditors (university degree & 3 years practical training). But for some qualifications the education threshold is lower, which is then often combined with longer practical training (e.g. 7-10 years in Germany). So how long it takes to qualify often depends on the level of education the trainee has.

Unlike for auditors, there are no EU legal requirements on registration, professional bodies or oversight for accountants or advisors. Therefore, there are differences on national level. For example, accountants may be subject to oversight in one country while they are not in another.

[1] Available at https://www.iaesb.org/publications/2019-handbook-international-education-standards